2024-2025 Layens Bee Sources Survey – Part 2

- Posted

The March 2025 part 1 survey focused exclusively on colony losses over the winter of 2024-2025. The question was how beekeepers faired, using the Layens hive style (26%), in comparison to the extensive 62% colony loss rate reported by commercial Langstroth beekeepers. The intent of part 2 was to dig deeper into the conditions and sources of the honey bees in Layens colonies to see if any insights might be gathered that helps explain their low loss rate.

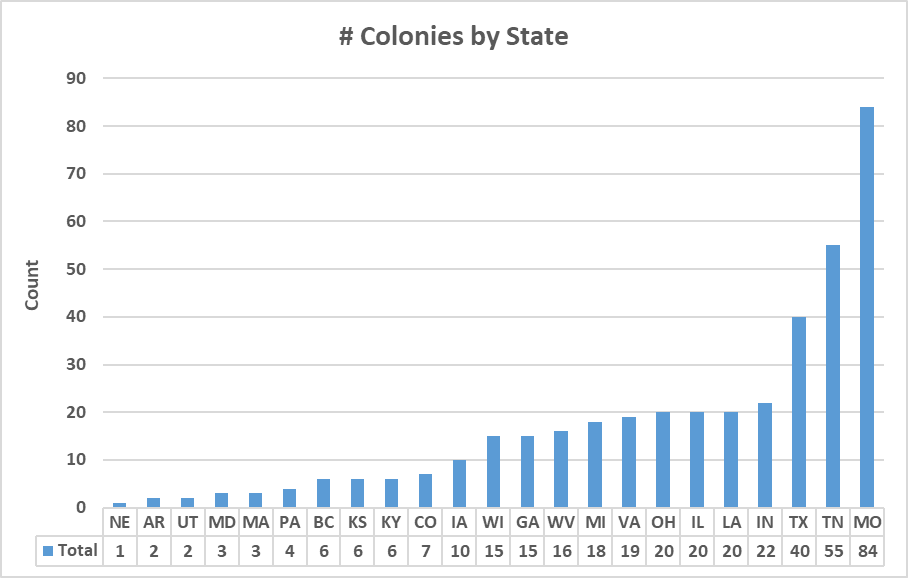

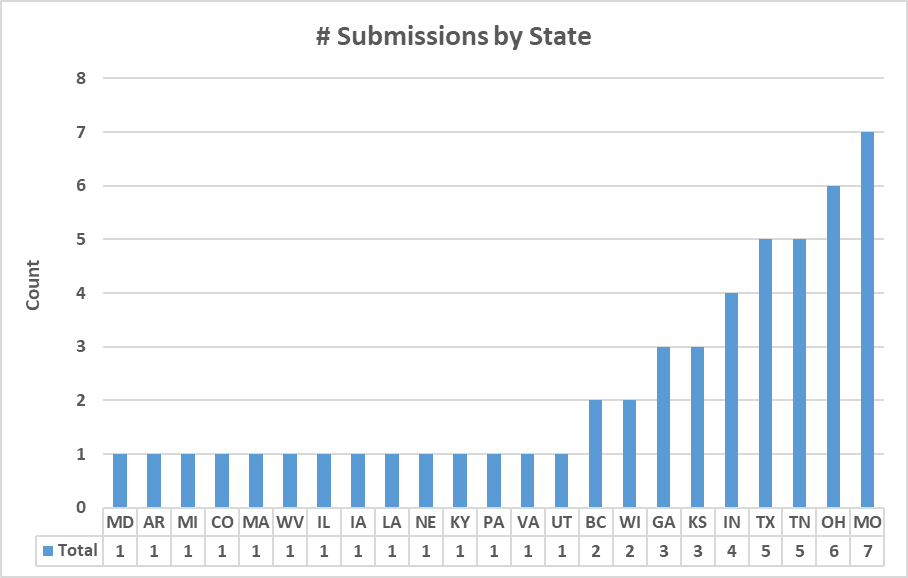

Many data points were gathered from beekeepers across the USA and a couple from British Columbia Canada representing a total of 51 apiaries and 394 colonies. Many of the responses were from apiaries with 10 or less colonies. With over half of the total apiaries located in backyard settings (subdivisions or large lots).

Apiary information was collected about location, physical setting of the apiary, acreage, type of foraging, foraging quality, water sources, honey bee sources, swarm trapping, splitting methods, and the success of beekeepers 2024 swarm trapping, splits, and nuc purchases. This is a single year analysis (2024) and does not include trends, but the survey will be posted annually in March of each year going forward and future reports will include trending. Below are the results of the survey.

Submissions

Most of those using the Layens hive style are located from Texas eastward to Virginia. Likely this isn’t related to weather or foraging conditions but more about early adoption that could have sprung from conferences and influencers surrounding Missouri over the last 7+ years. The spread of its popularity seems to be very organic but is also likely driven by a growing desire by some beekeepers to look for ways to work more closely with the natural honey bee lifecycle and behaviors – to move toward equipment and a management style believed to be closer to what the honey bees experience in a natural tree hollow. Its continued popularity across the US is a sign of its success in meeting beekeepers needs both for the bees and for themselves.

Location

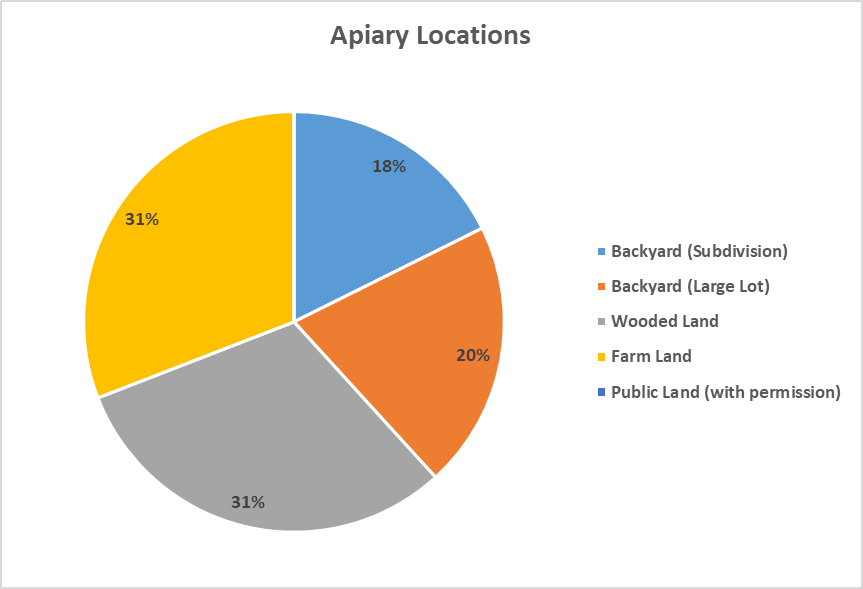

Apiary locations varied between beekeepers and some reported multiple settings for their hives but 38% of them reported keeping colonies in their backyards. This is very encouraging to know that they are keeping their bees close improving the opportunity for regular observations and benefiting their local environments. 62% were located in areas primarily used as farmland or considered wooded. I attribute this higher percentage to the types of land use in the states, employment, as well as the attitudes of the residence for which the Layens hive style might appeal to.

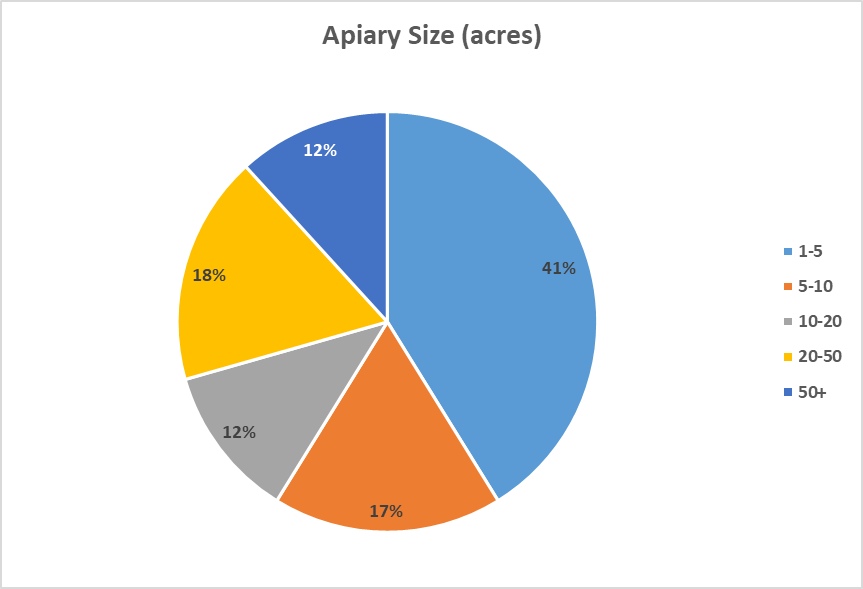

Land availability and acreage also mimic this same trend matching land size to the setting. Those with apiaries in backyard settings normally had less than 5 acers while farms and unmanaged land owners reported from 5 to 50+ acers.

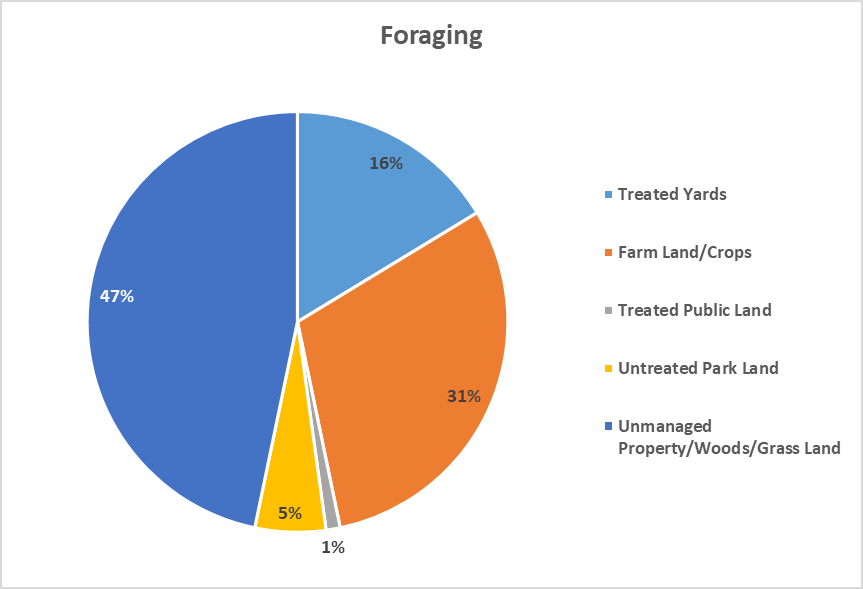

Foraging and Water

Given the association of good foraging opportunities to the health of a colony and honey production understanding the types of available foraging and conditions possibly associated with that land and water plays a part in understanding what makes a successful apiary location. Close to half of the land types reported were unmanaged, wooded and/or grass land. A third were farmland which could be a monoculture environment with some chemical and/or pesticide run off and 16% were yards that have weed treatments applied providing poor local foraging opportunities or in the case of farmland could actually be harmful to the bees at different times during the planting or growing process. Given that 53% of the apiary land could have some negative effect on foraging and/or on the bees while foraging the recent annual reported Layens loss average of 26% would suggest that foraging may not be as significant a contributor to losses though it certainly could be a weakening factor that is a vector for other factors facilitating a greater overall negative effect that leads to eventual loss in future years.

Overall foraging quality was reported as good to excellent. More investigation would need to be done to determine if this rating was given primarily because of the type of land reported and so an assumption that quality foraging opportunities should be available or if a conscientious review of the plants available in the area was done. Given that 47% is reported as unmanaged property its likely that a variety of plants could have become established as a source of quality foraging. Farmland could be another possible source of abundant foraging but often the perimeter hedge rows, and tall grass areas are being removed to open more space for cash crops either eliminating foraging spots all together or pushing this into wooded land that would only support certain shade loving plants along or within the trees.

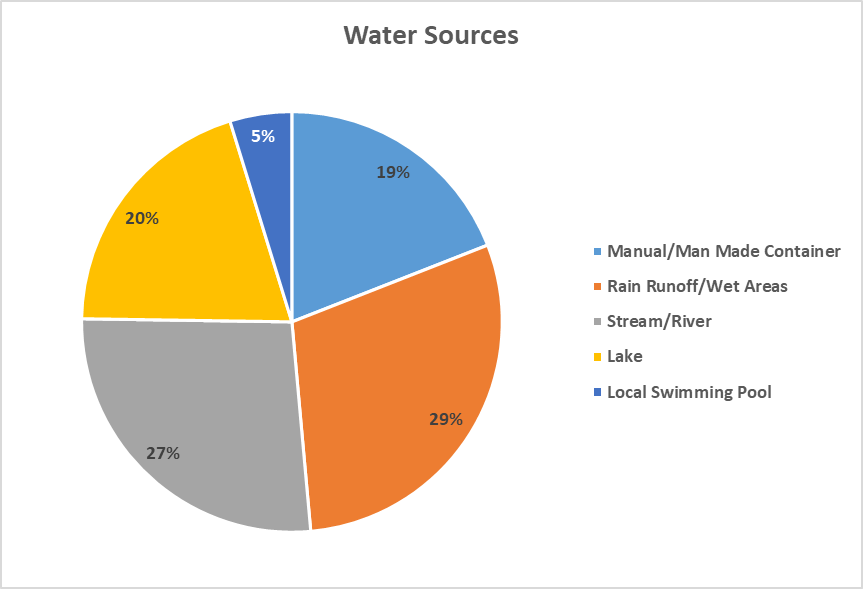

References to water sources and what they might contain that could be harmful to honey bees is not often mentioned in studies. Water though plays a significant part in the life of a bee and the work they do throughout the colony lifecycle from their own bodily needs, to honey production, to what moisture is part of the food fed to larvae. Chemicals that have leached into their water sources could be as impactful to the colony health as the quality and availability of pollen and nectar so its important to take stock of what they can reasonably access.

47% of reported water sources (streams, rivers, and lakes) could provide conditions that disperse or dilute harmful chemicals, but they might also be where more chemicals first enter the water system from run off based on the surrounding land use or be locations of direct dumping from municipalities or corporations. It is interesting to note that only 19% of beekeepers provide a controlled manual water source or rely on what are seen as natural sources such as 29% reporting rain.

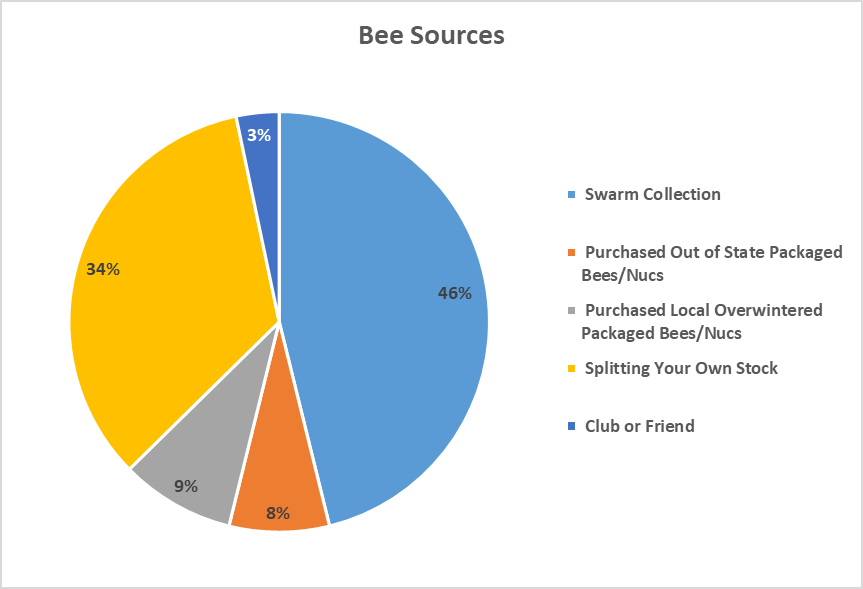

Honey Bee Sources

The sources for bees generally fell into two camps that together indicate an attempt to disconnect from normal commercial sources or importation and they lean more toward local and/or natural sources. 80% of Layens beekeepers, those that collect swarms and split their survivor stock, are trying to work with wild, feral or at least locally adapted honey bees. This reflects a growing belief (that is also supported by more resent research) that bees need to be allowed to evolve their own natural defense responses to viruses vectored by Varroa which treatments do not allow. Varroa are continually going through their own fast paced evolution cycle with the strongest of them surviving treatments making them even harder for the beekeeper to address. On the positive side, studies are identifying colonies in multiple continents as well as North America that are free living and showing the ability to manage Varroa populations and the viruses they carry. It is possible that with 46% of the Layens beekeepers utilizing swarm collection to expand their apiaries they are tapping into this wild, feral, or local populations potential.

Hygienic behavior and virus resistance is often an elusive set of genetic traits to select for and can be quickly lost when bringing a wild or feral swarm into an existing apiary. This is likely caused by excessive mite counts in neighboring colonies that don’t have these genetic traits, which exposes the newly added swarm to an overwhelming level of Varroa even with some Varroa resistance. Resistance is not an on or off switch but a combination of both physical behaviors and immune system defenses all responding to an array of environmental stressors and genetic triggers. It is still unknown whether the queen alone or a combination of the queen and drones during mating provide these genetics to the next generation of workers and daughter queens.

In the wild this beneficial gene pool is maintained through evolution and survival increasing the possibility of important specific genes being available for the next generation, but many beekeepers prop up weak genetics through treatments and expose resistant daughter queens to drone genetics from non-resistant stock. Selective breeding can also impact the availability or lack of these genes from a time in their evolutionary past blocking the opportunity to be expressed again.

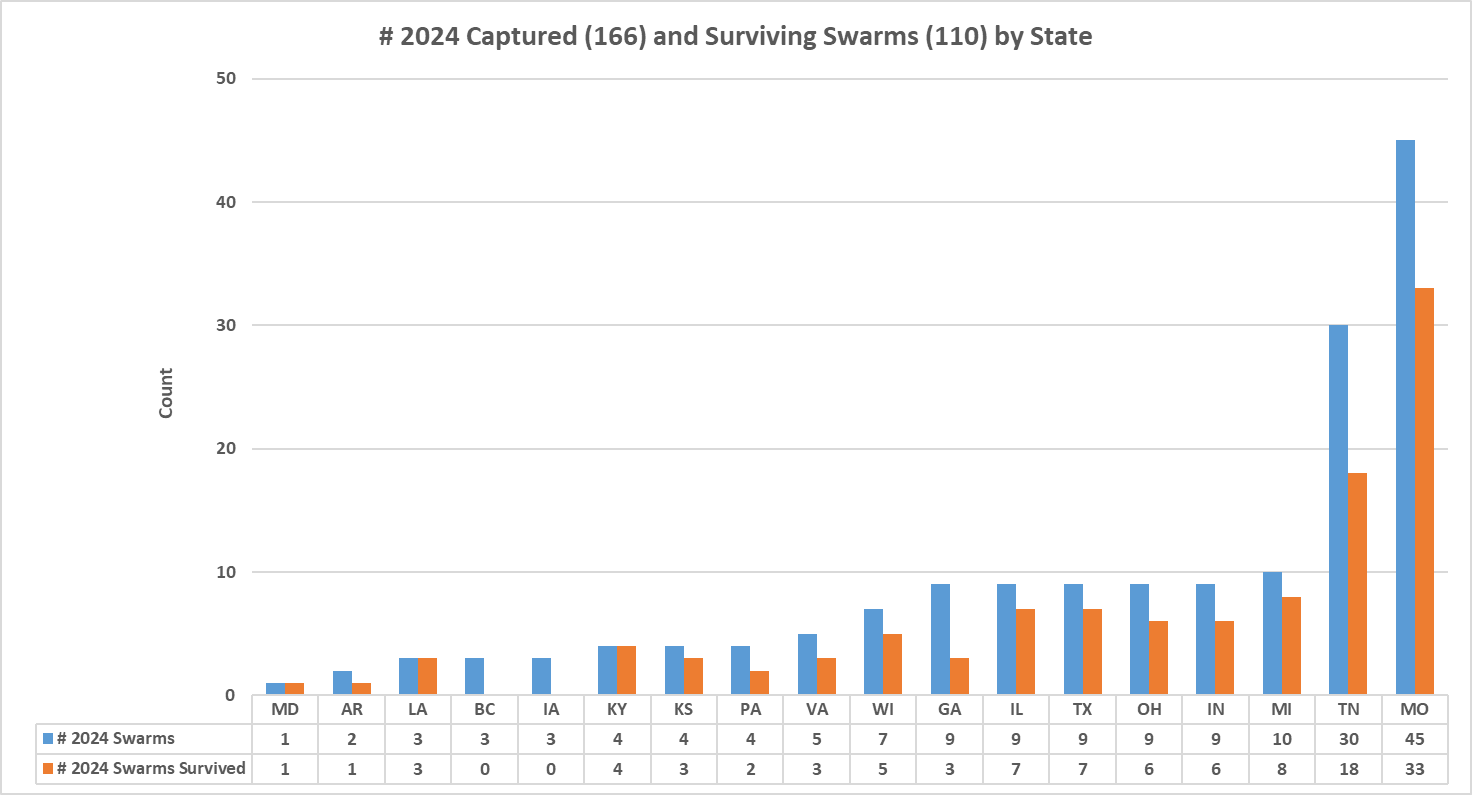

Swarm Collection

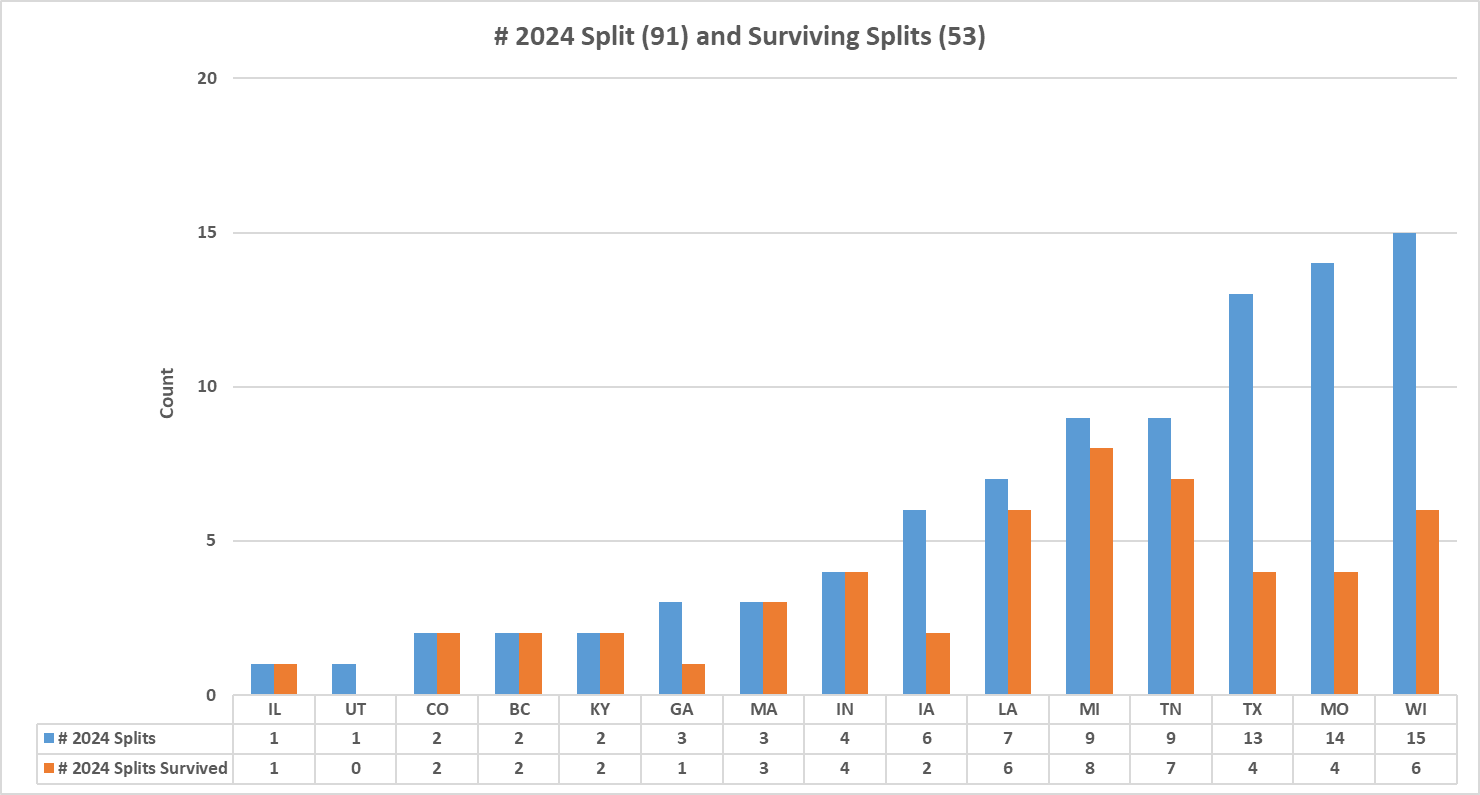

Of all beekeepers who reported collecting swarms in 2024, 66% of these swarms came through the winter in a good to excellent condition. This percentage is above the 50% swarm survival that Dr Seeley suggested for swarms who select a natural new home, and the remaining 34% loss is certainly less than last year’s national commercial loss percentage and for the last few years. As usual the more swarms collected the more this drives up the actual number of losses per state.

There is a significant jump in the number collected in Tennessee and Missouri than other states. This might indicate more rural apiary settings and sites of opportunity or more willingness of the local beekeeping community to encourage and support local beekeepers in trying this method. Given the good success rate, swarm collection certainly seems to be a low cost and effortless way to replenish winter losses. The learning curve is easy to get over and after the first year the cost is almost nothing especially compared to the purchase cost of a new package or nuc.

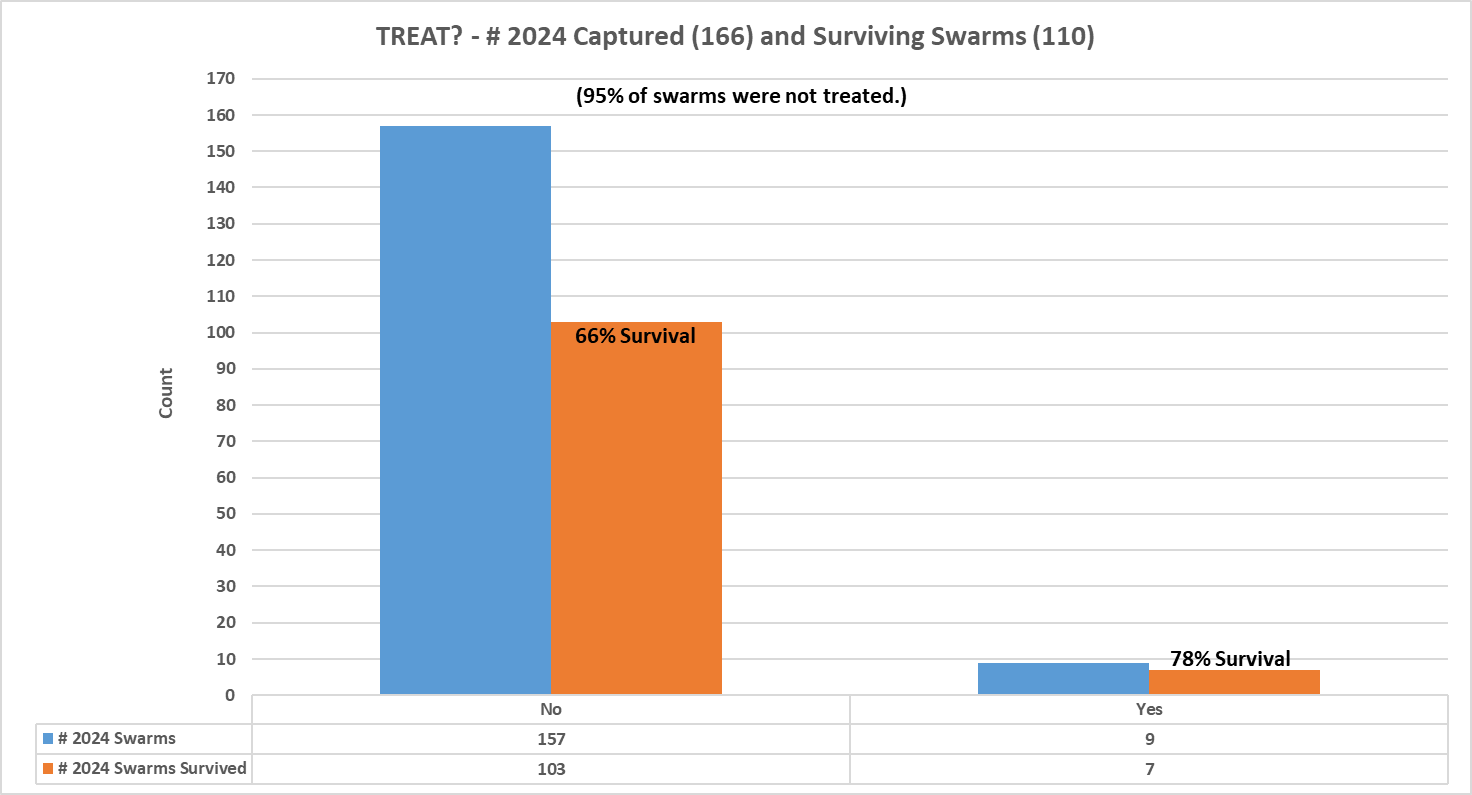

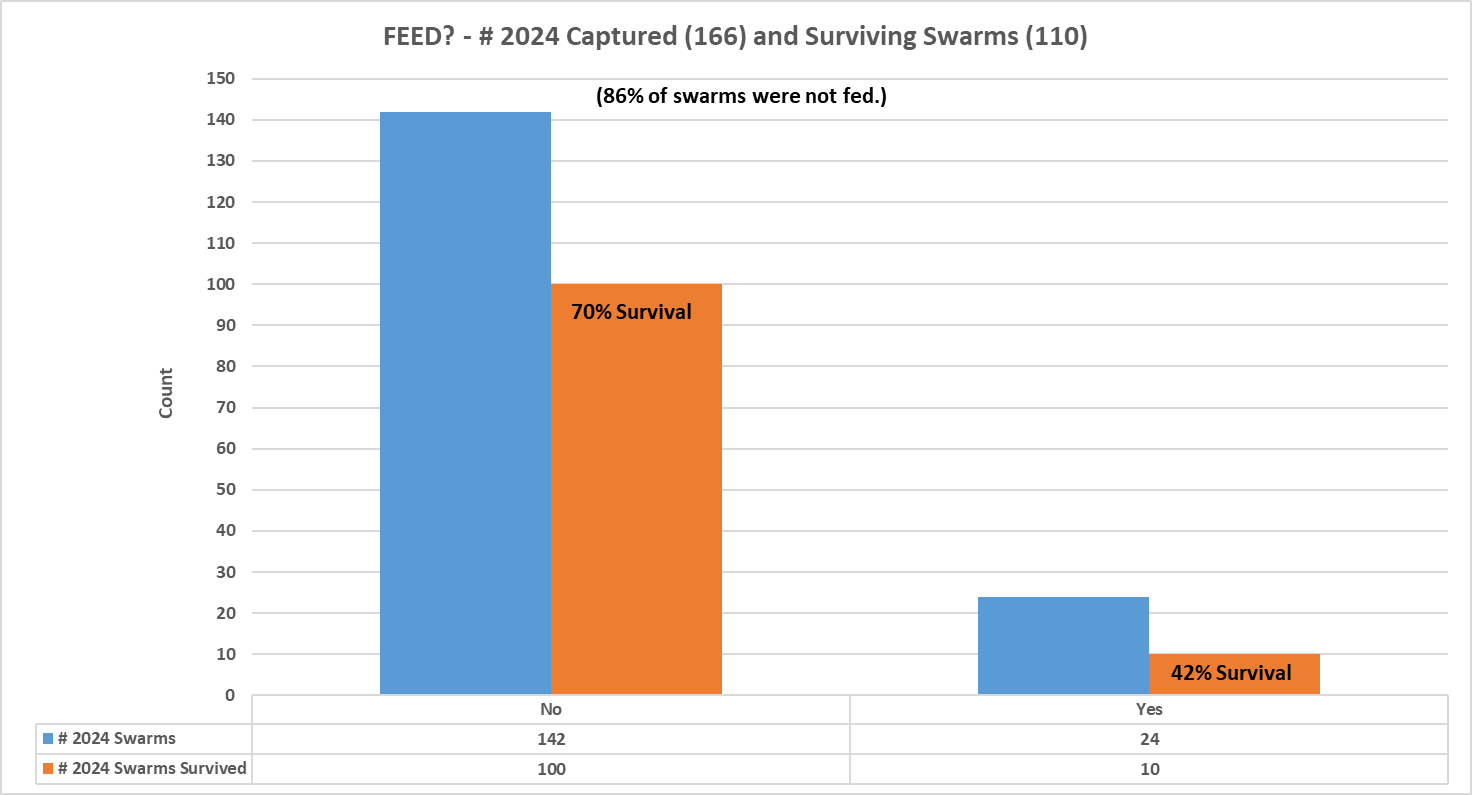

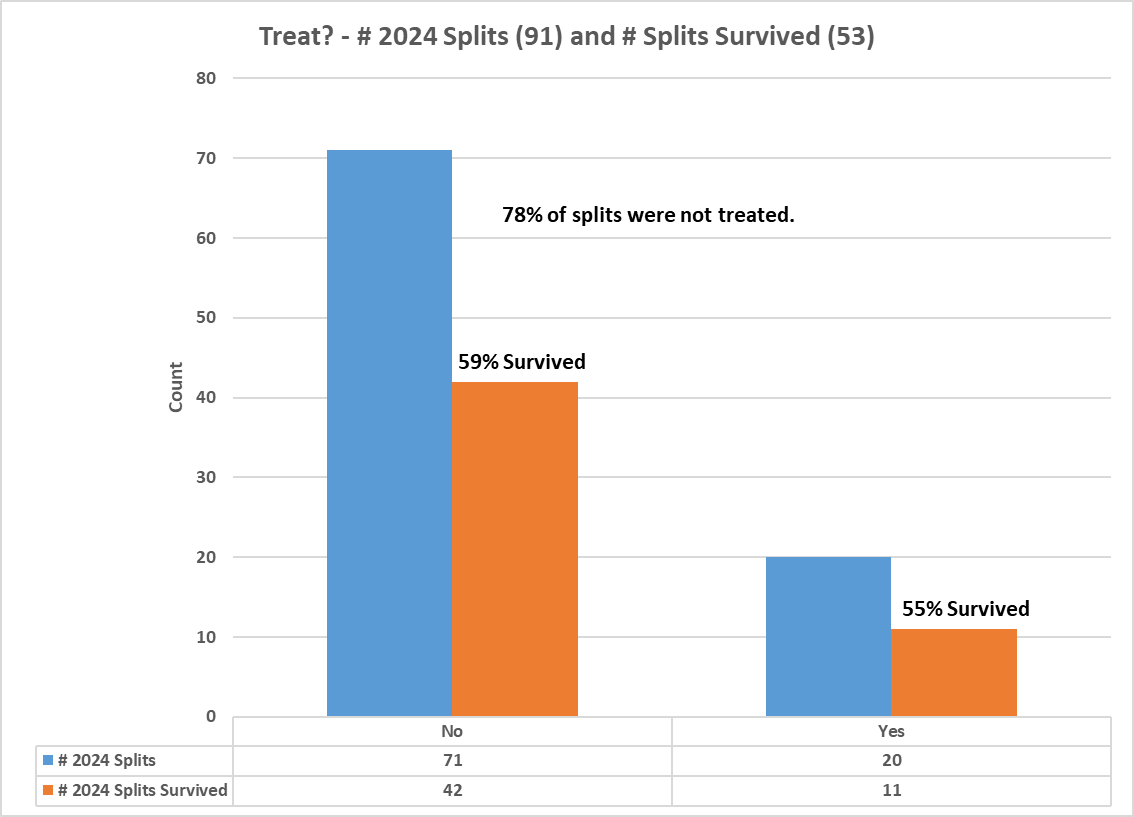

As can be seen from the charts below neither treating nor feeding had a significant positive effect on the 66% survival rate. In fact, most beekeepers did not treat or feed their swarms which makes sense for a couple reasons. Given these are hopefully wild or feral colonies treating an overwintered colony that has shown some level of Varroa resistance could in fact hurt them and diminish their early spring build up simply by the application of the treatment. Queens and workers have varying resistance and immunity profiles to different chemicals. The queen’s immunity is more pronounced in her reproductive organs while the workers immunity favors those organs that come in contact with pollen and nectar through foraging work. The queen is also rarely outside the hive and is fed royal jelly. These differences in physiology alone could begin to explain recent issues with queens dying and/or absconding who are coming into contact with treatments. Now it could be pointed out that a certain chemical during testing did not kill a colony or queen but there are few if any studies that look at the long-term effect on the queen’s egg laying which may largely be missed since most commercial beekeepers requeen on an annual basis obscuring possible treatment effects on older queens. Given the queen rearing market and the propensity of commercial operations to requeen annually its unlikely this kind of long-term study would ever be done at a university, hopefully I’m wrong.

Also, as a new swarm they are full of nectar and ready to build comb as quickly as possible in their new home so the queen can begin laying. It will be a good 21 days or more before any workers emerge. Feeding at this time might cause the swarm to honey bound the queen removing important comb for eggs that the swarm needs to expand their numbers and establish themselves. Most survey respondents reported good apiary foraging and water sources so their collected swarms should be successful in providing for themselves. Feeding later might be a better solution once the colony is established and based on foraging conditions later in the summer in preparation for winter.

Splitting

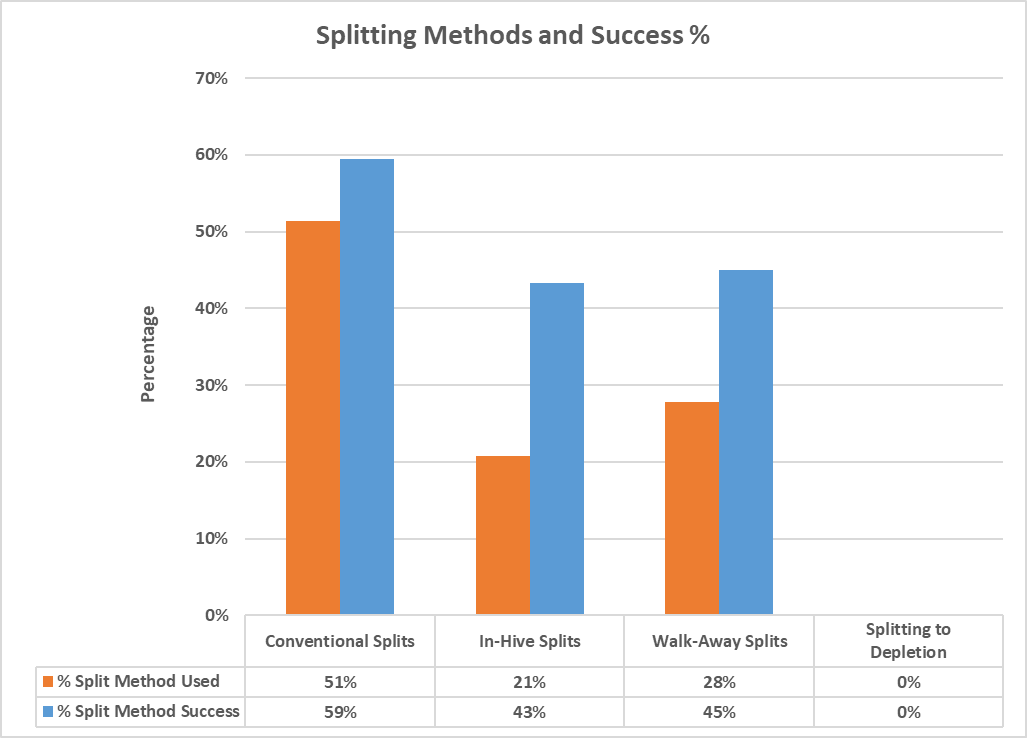

Overall, Conventional Splits (moving the queen and some brood to a separate hive) was the preferred method based on responses. Walkaway Splits (splitting into two hives without finding queen) came in second and might be popular given the difficulty of finding the queen in a full hive who may also not be marked. Both methods appear successful likely contributing to their popularity.

States showed varying success rates in expanding an apiary through splitting but compared to swarm collection had only a little over half the attempts. This may have something to do with the foraging and weather conditions in these areas but also may reflect those who simply favor swarm collection as their primary winter recovery method. Practice makes perfect is the old saying and those who are focused on swarm collection might not be as skilled or interested in splitting. Swarm collection might also click with those who want a simpler process that can provide a sense of excitement of catching something – like fishing or hunting.

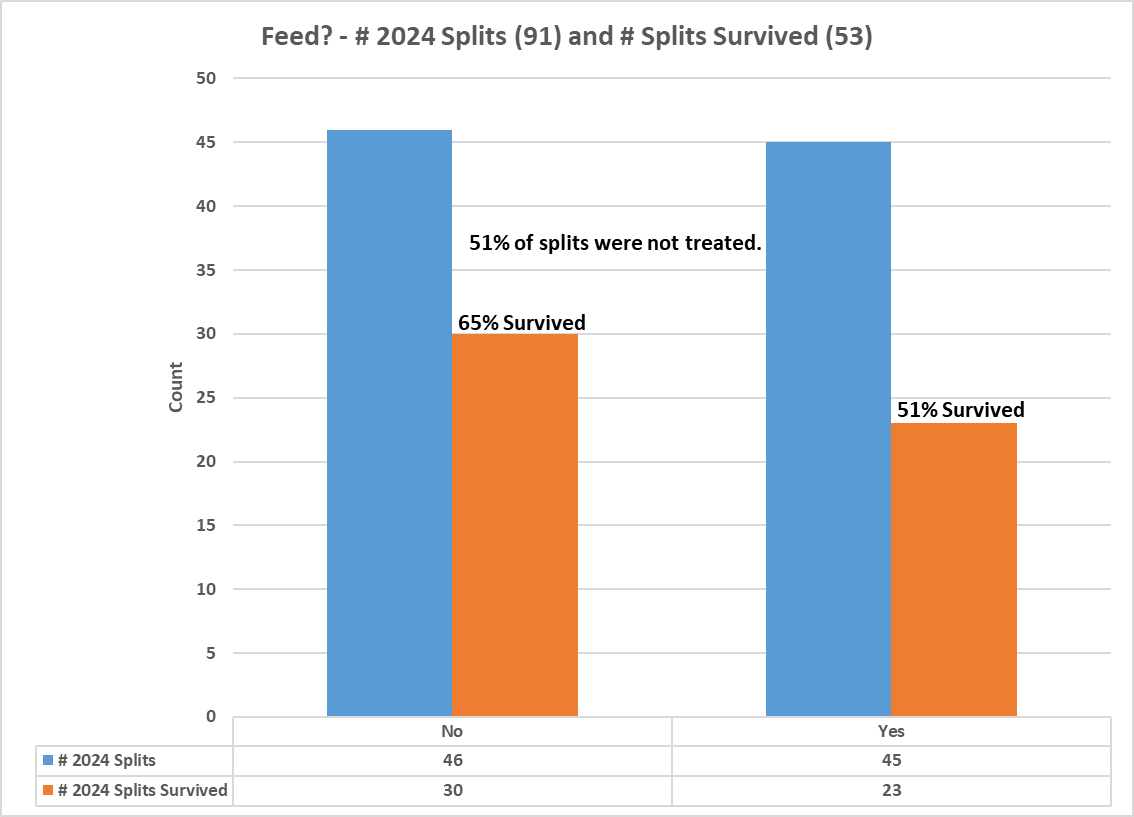

Treating and feeding splits did show some differences compared to providing the same for swarms which could be attributed to the starting condition of the colony being split. Swarms are prepared for the change and have the resources and energy to respond to the event while splits are not anticipated and rely more on the beekeeper’s management of brood frames and resource frames (honey/pollen). This in not to say that splits can’t be successful without treatments and/or feeding. The 59-65% success rates for no-treated and no-fed splits respectively show this but the question is really the condition and preparedness of the colony in the face of a significant disruptive event. The results do seem to indicate that feeding was more impactful than treating.

It would be interesting in the future to dive deeper and determine which part of the split benefitted more. I would suggest that those colonies weakened by Varroa might see more success in the half that has the queen and doesn’t go through a brood break. The brood break of the other half should help knock back the Varroa without treatments. Feeding on the other hand might help both sides of the split if enough resource frames aren’t available or foraging is poor. Remember the workers are not full of honey as the split is completed. The splits will rely greatly on the resources frames which are made available to them. This is all speculative but generally makes sense when considering the differences between the starting conditions of swarms and splits.

Nucs

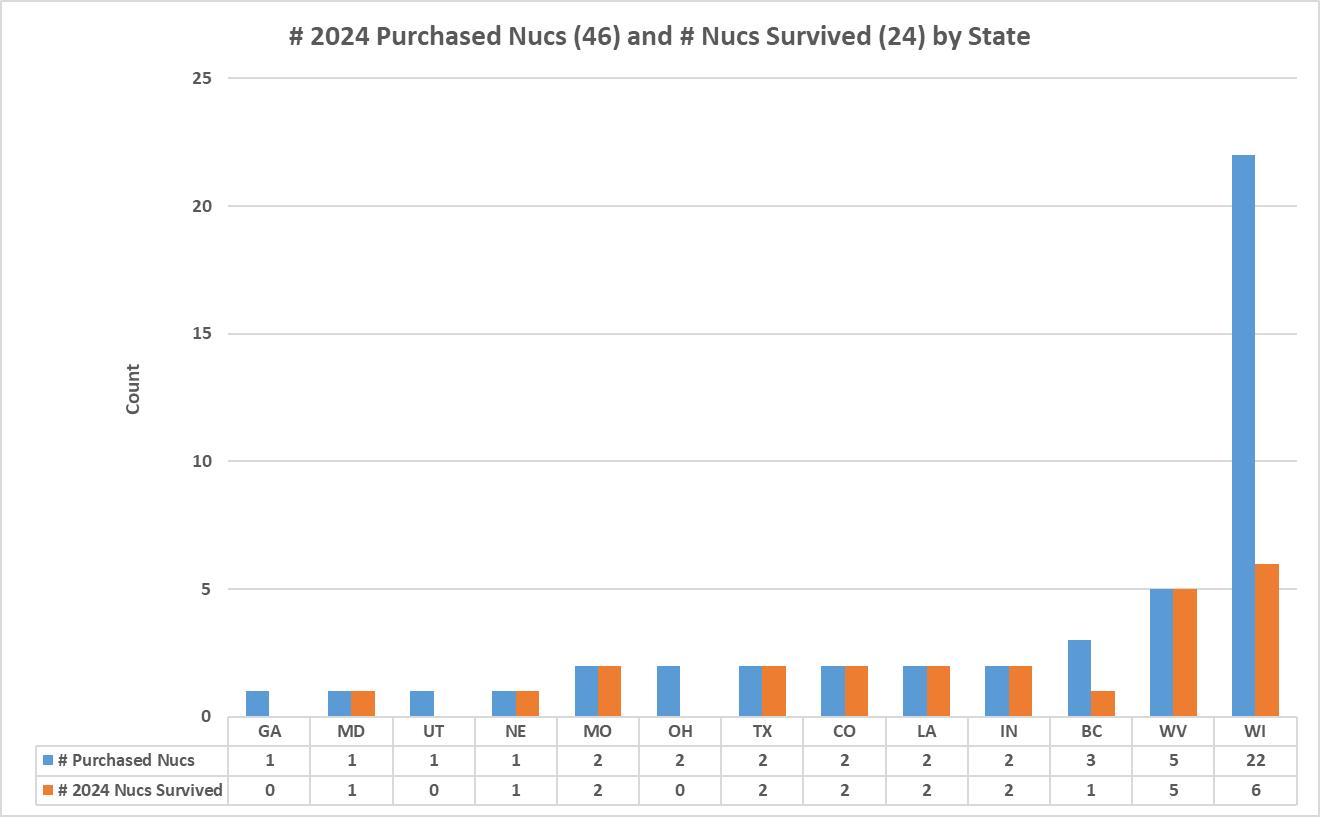

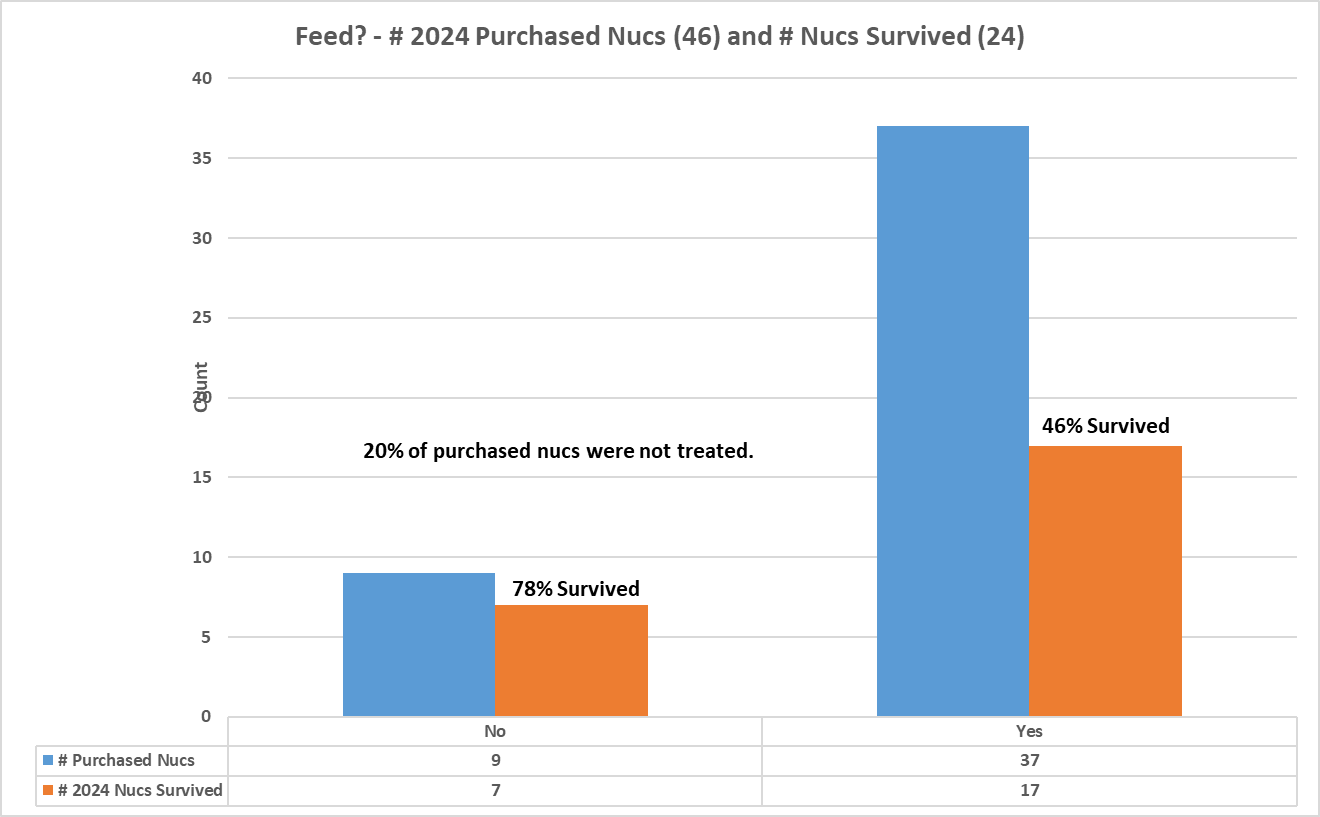

Most of the small number of purchased nucs were in Wisconsin. There’s no indication why this was the case but no matter where the purchased nucs ended up only 52% overall survived our past winter and of the three choices for recouping losses this was the least sought after. Wisconsin alone only had a 27% survival rate with purchased nucs while swarm collection was the most successful at 71% survival for the state.

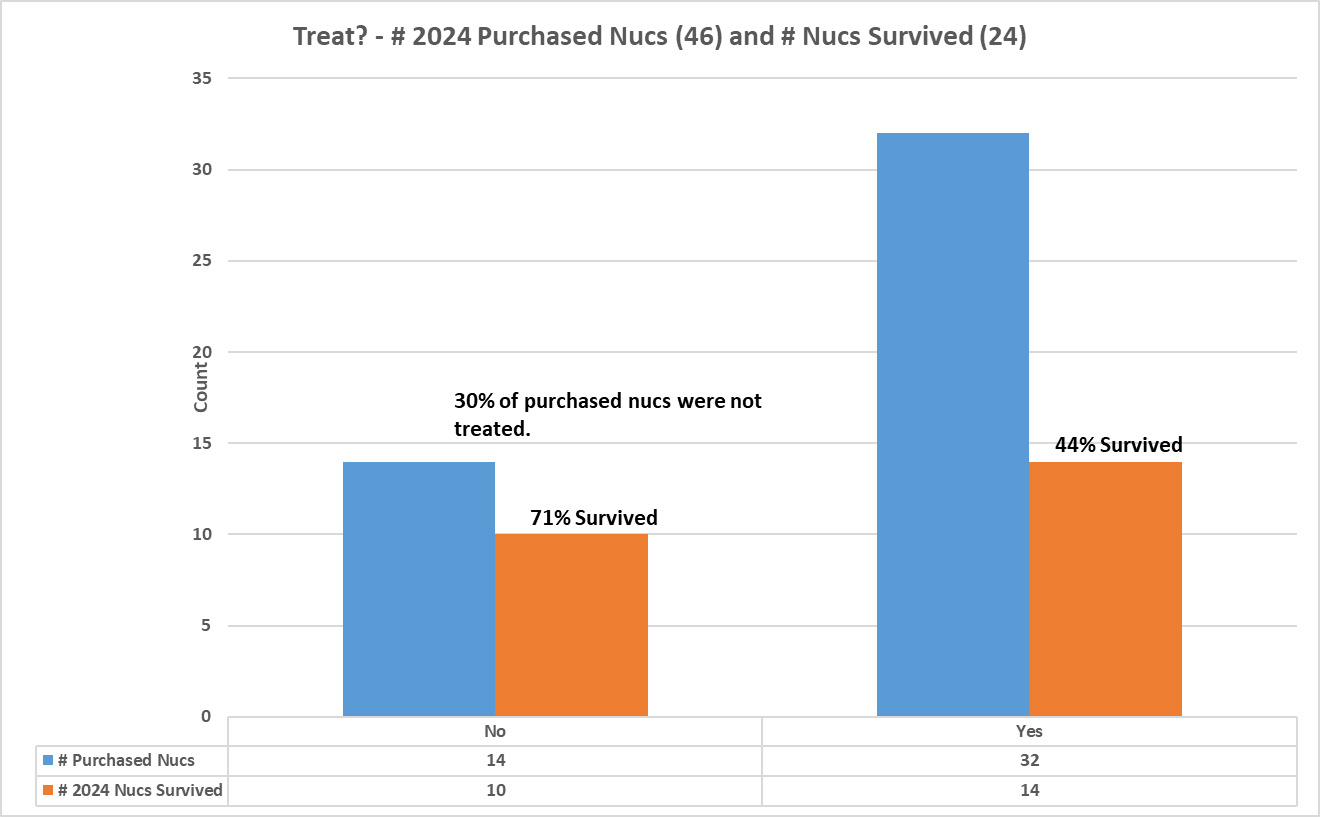

Nucs are also where we see the highest percentage of treatments and feeding by beekeepers but sadly this did not improve survival rates. Over 50% treated and/or fed died while those who weren’t had a significant increase in survival well above the national average. Why might this be the case? Could the quality of the received nucs play a part? Maybe the parent commercial operation also saw significant 2024-2025 winter losses. This last point though a possible explanation especially for the Layens beekeeper who followed a similar management regiment doesn’t truly explain why not treating or feeding shows better colony survival. Other factors such as local weather, foraging, water, and hive style are the same. Could it be the quality of the feed verses natural foraging or even unknown detrimental effects of the treatments? At this point the data doesn’t shed any light on that topic.

Conclusions

In general, Layens beekeepers locate their hives in medium sized apiaries, on land that has good opportunity for quality foraging, and access to clean water (from natures perspective). In addition, apiaries often have access to unmanaged, wooded, and/or farmland with larger sources of water such as lakes and streams. This is likely the conditions for many apiaries in these states whether Layens or Langstroth hives are used.

What seems to be a much greater differentiator is what the sources of the bees are. There is a strong preference for natural and/or local sources with this community and it appears to be a successful choice. Swarm collection also appears to be the best and most successful means for recouping or expanding spring colonies and the data also indicates that there’s no significant impact to colony survival of not treating or feeding. In fact, combining these management processes with a hive style that is also beneficial to the bees and beekeeper may be a way to bring back the “hobby” of beekeeping making it a simpler and more enjoyable experience for those not looking to be commercial operations.