Epigenetics: Honey Bee’s Gene Response

- Posted

Epigenetics

In biology, epigenetics is the study of heritable traits, or a stable change of cell function, that happen without changes to the DNA sequence. The Greek prefix epi- in epigenetics implies features that are “on top of” or “in addition to” the traditional genetic mechanism of inheritance. Epigenetics usually involves a change that is not erased by cell division and affects the regulation of gene expression. Epigenetics is like someone taking a pencil and crossing something out—or adding something—on a blueprint, saying, “don’t make that here, make it over there.” And that’s a good analogy because, unlike the messages encoded in a DNA sequence, the messages that epigenetics communicate are reversible and changeable. That allows adaptability; genes can be expressed in specific places, at specific times, and in response to specific signals or cues.

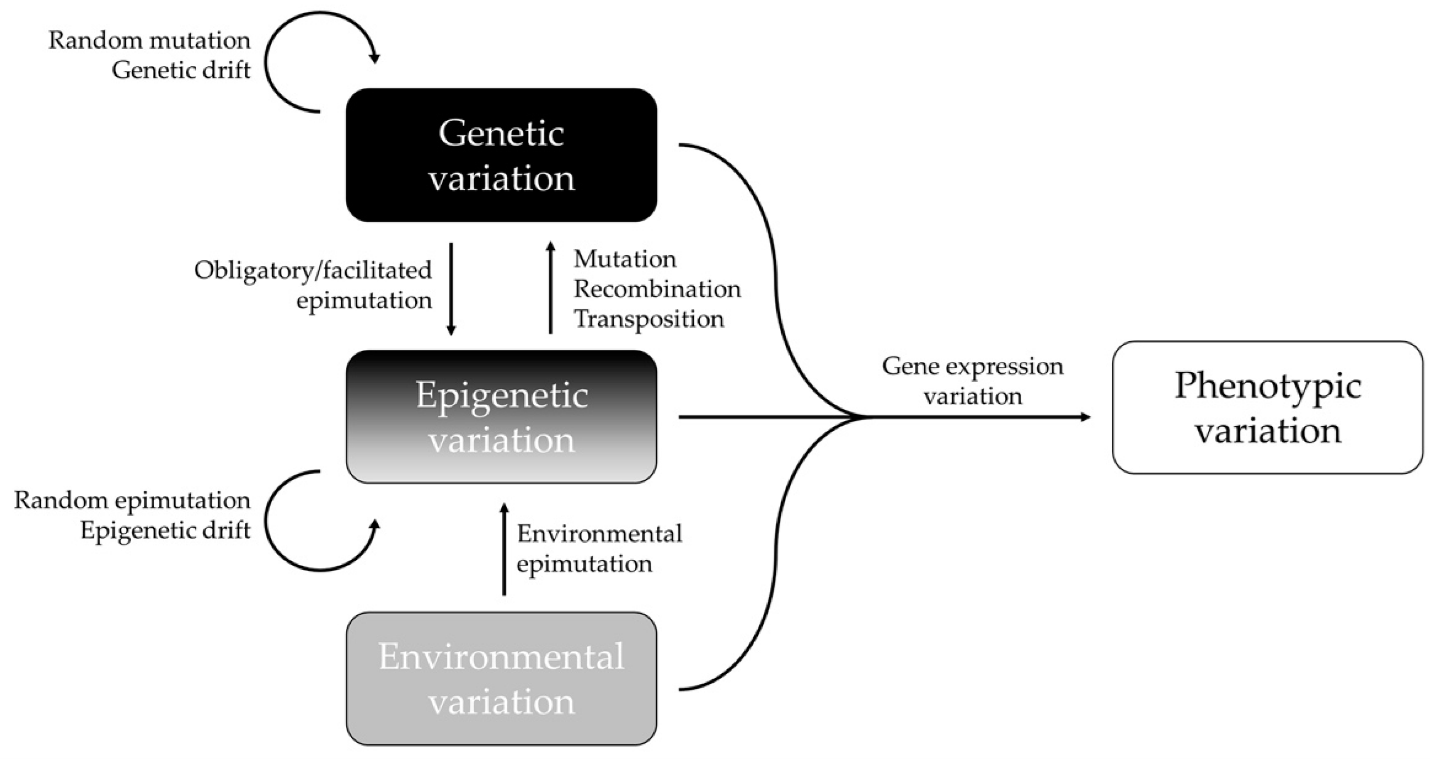

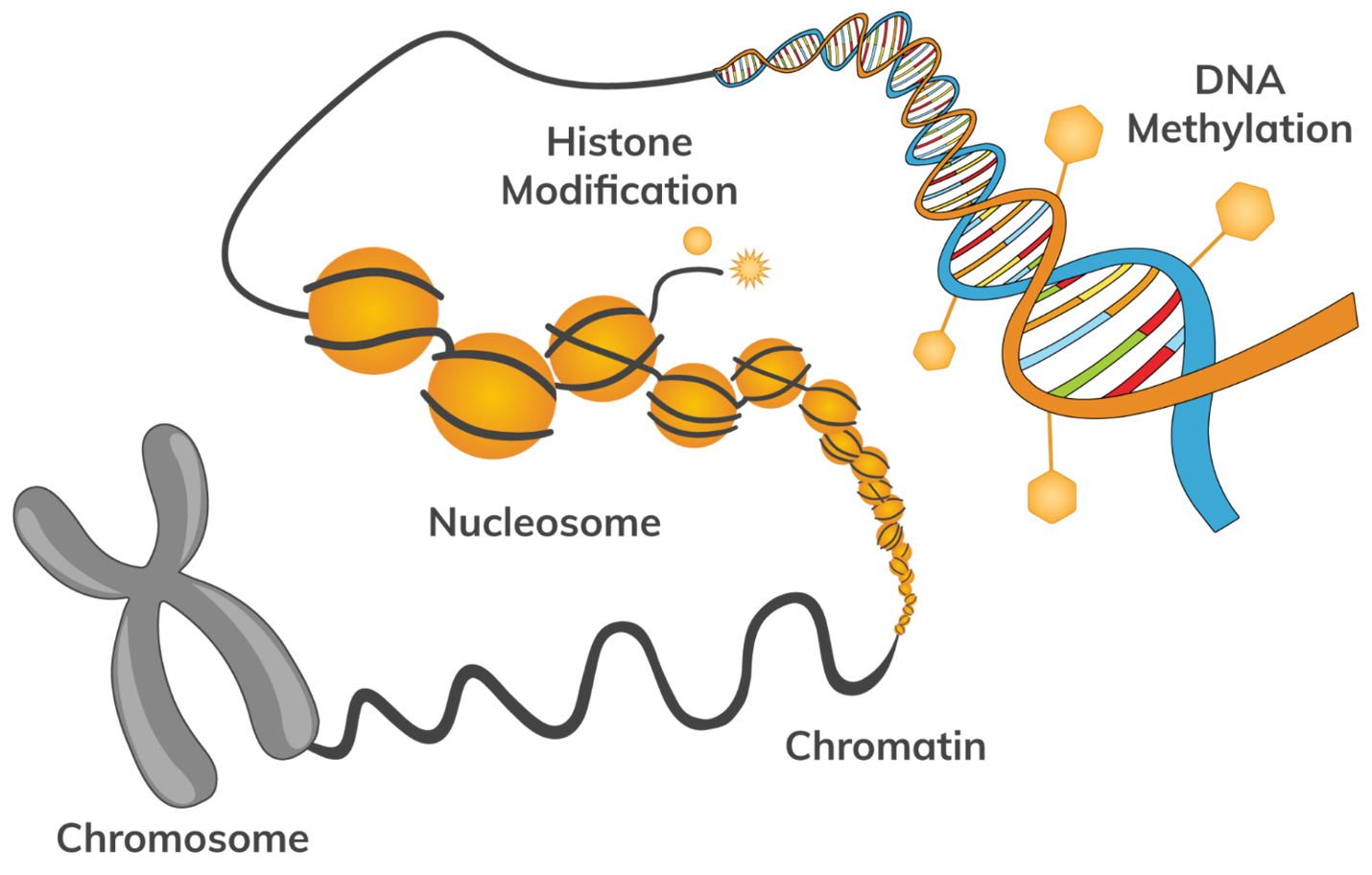

Epigenetic mechanisms are central to gene regulation, phenotypic plasticity (change to observable physical or biochemical characteristics of an organism), development and the preservation of genome integrity (organism’s genetic material). There is growing appreciation that epigenetic variation makes direct and indirect contributions to evolutionary processes. First, some epigenetic states are transmitted intergenerationally and affect the phenotype of offspring. Second, epigenetic variation enhances phenotypic plasticity and phenotypic variance and thus can modulate the effect of natural selection on sequence-based genetic variation. Third, given that phenotypic plasticity is central to the adaptability of organisms, epigenetic mechanisms that generate plasticity and acclimation are important to consider in evolutionary theory. Fourth, some genes are under selection to be ‘imprinted’ identifying the sex of the parent from which they were derived, leading to parent-of-origin-dependent gene expression and effects. These effects can generate hybrid disfunction and contribute to speciation. Finally, epigenetic processes, particularly DNA methylation, contribute directly to DNA sequence evolution, because they act as mutagens on the one hand and modulate genome stability on the other by keeping transposable elements in check. Methylation is the process of adding a methyl group (CH3) to a molecule, often DNA, which can change the activity of a gene without altering its sequence. This process plays a crucial role in regulating gene expression and is a key mechanism in epigenetics.

Phenotypic Plasticity

Phenotypic plasticity can be defined as the ability of individual genotypes to produce different phenotypes when exposed to different environmental conditions. This includes the possibility to modify developmental trajectories in response to specific environmental cues, and the ability of an individual organism to change its phenotypic state or activity (e.g. its metabolism) in response to variations in environmental conditions.

Phenotypic evolution depends on phenotypic variation, and in metazoans (includes all animals except sponges), as in other multicellular organisms, phenotypic variation (when not explicitly restricted to a given developmental stage) is variation in developmental trajectories throughout the ontogeny (organism’s lifespan). An individual organism’s trajectory is the result of a unique interaction between its genome(s), the temporal sequence of external environments to which it is exposed during its life and random events at the level of molecular interactions in its tissues. Thus, ‘development is larger than just developmental genetics’, and there is a plethora of environmentally induced components of developmental variation that are relevant for both the ecology (interaction with the environment and other organisms) and the evolution of a species. As proximate causes of phenotypic variation, genes and environment are thus inextricably linked.

From the point of view of the adaptive evolution of plasticity, a significant distinction can be drawn between direct and indirect effects of the environment on development. In the first case, plasticity is due to the effects of environmental variables that directly affect a developmental or a physiological process (e.g. temperature can directly influence developmental processes affecting chemical reaction kinematics and the physical properties of membranes). In such situations, plasticity is possibly non-adaptive. Conversely, we speak of indirect effects when the environmental cues elicit responses that are mediated by other physiological and developmental events. In this way, the environmental conditions that induce a given phenotype do not need to be the same conditions to which the phenotype is an adaptation (e.g. photoperiod, altering the pattern of hormone secretion in insects, can elicit a change in the developmental pathway that leads to the production of the phenotype best adapted to cope with the coming temperature and nutrition conditions). This provides scope for a time delay between the eliciting signal and the developmental response, so that the former can actually perform as a predictor of a forthcoming selective regime.

DNA

The genome, epigenetics, and gene expression are all interconnected because, ultimately, gene expression is all about anything that will impact or control the ability of a cell to express a piece of its genome. Historically, the fields of gene expression and epigenetics were somewhat separate because the mechanisms of epigenetics were not really understood. But in the last two to three decades, that all changed. Now, when we talk about a piece of DNA and how that gene is regulated, we have to figure out if it’s regulated through DNA sequence, epigenetics, or a combination of both. Usually, it ends up being both.

Though the investigation of the role of DNA methylation in developmental plasticity has thus far been limited to species in which the genome is well characterized, and assays are available to conduct epigenetic analyses, it is evident that epigenetic control of gene expression is an across-species phenomenon. Moreover, the emerging evidence from species ranging from honeybees to humans suggests that environmentally induced changes in DNA methylation may serve as a mechanism mediating developmental plasticity leading to phenotypic variation. Considered within an evolutionary perspective, it appears likely that these mechanisms are a fundamental feature of the process of adaptation to the environment, leading to adaptive reproductive, behavioral, and metabolic strategies which promote survival. The ability to transmit these developmental effects across generations raises important issues regarding the mechanisms of heritability and the ancestral origins of phenotypic variation.

Evolution

Two recent findings have radically expanded the possible role of epigenetics in evolution and ecology. Firstly, in some situations, environmental cues can influence epigenetic programming and secondly, this information has the potential to be passed on to the subsequent generations via the gametes. This expanded view raises the possibility that these marks may be able to produce genetic change over time periods that may be relevant to evolution. The idea that epigenetic marks may carry gene expression changes across generations, probably in a limited way, is of importance in our understanding of the genetic assimilation of acquired traits.

Workers or Queen

Within a beehive, there are several discrete and distinct castes, with the highest being the queen bee and the worker bee being below it. These two types of bees have drastically different roles in the hive and look drastically different; but strangely, they are genetically similar. The queen bee is larger and lives longer than worker bees. Queen bees are the only fertile female bees in the entire hive. So, with the help of drones, (another type of bee whose sole purpose is to procreate with the queen,) they create viable offspring that are all genetically similar because they all share genetically similar sperm from the male bees.

the only difference between the worker bees and the queen bees is the turning on and off of certain genes through nutrition. The epigenome is created through a process called methylation: the covalent bonding of small methyl groups onto the cytosine that allows for genes to be turned on and off. These genes encode for different proteins that make up the physical form of the bees. By eliminating or turning off different sequences, the physical makeup of different features is being altered.

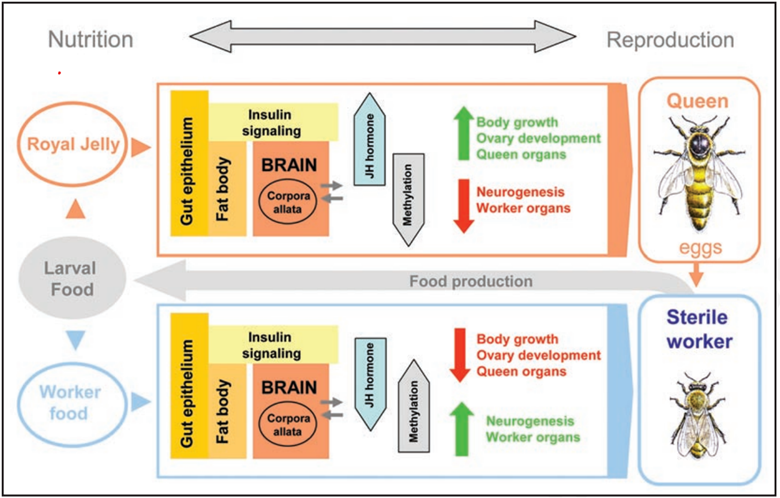

In the honey bee, queen and workers have different behavior and reproductive capacity despite possessing the same genome. The primary substance that leads to this differentiation is royal jelly (RJ), which contains a range of proteins, amino acids, vitamins and nucleic acids. MicroRNA (miRNA) has been found to play an important role in regulating the expression of protein-coding genes and cell biology. It all comes down to the food. After birth, if the worker bees determine that a new queen is needed, they randomly pick one of the larvae and feed it royal jelly instead of pollen and honey like all worker bees and drones. Royal jelly is known as bee milk. It looks like “white snot” and is made of mostly water with combinations and sugars. It is secreted by the heads of worker bees.

Royal jelly is different than regular jelly, pollen, and honey of the worker bees because it has a different ration of mandibular to hypopharyngeal gland secretion. This means that it has no detectable trace of phenolic acid, which comes the flavonoids in the from the plant products eaten by regular worker bees. These flavonoids increase the immune responses of adult worker bees in regular pollen and jelly, which allows for them to have a strong immune response and work for long periods of time while the queen lack this. This also helps worker bees detoxify pesticides faster. Royal jelly also has an enzyme that inhibits the protein DMT 1 methyltransferase, which demethylates (deactivates) an entire subset of genes in the larvae, allowing for it to develop into a queen. This also allows for the development of chemical protection of the queen’s ovaries, sheltering the toxic or metabolic effects of plant chemicals. This then allows for the queen to remain fertile while leaving the worker bees sterile. This decision is made upon the first feeding so the queen would never be fed pollen as a larva and damage her immune system.

One would think that feeding the larvae royal jelly is what makes it into a queen; but rather, is the nutritional castration of withholding royal jelly from the worker bees that makes her the queen by isolating her. The royal jelly diminishes the toxic effects of pollen and honey on the reproductive system. Interesting to consider that the phenomenon of queen failure discussed over the last recent years might have been the result of beekeepers treating colonies with chemicals and believing the queen to have the same immune response to chemicals as the worker bees do. Without the workers immunity and associated detoxification ability the queen is actually more susceptible. Maybe this is why she is not lasting, dying and/or absconding while the workers appear to be just fine.

Caste

Eusocial insects can be defined as those that live in colonies and have distinct queens and workers. For most species, queens and workers arise from a common genome, and so caste-specific developmental trajectories must arise from epigenetic processes. Queens produce most or all of the eggs, while workers are either totally or partially sterile. Workers reproduce either vicariously by rearing their sisters and brothers—the offspring of the resident queen—or, rarely, directly. Studies have suggested that methylation is the primary mechanism by which Q-W dimorphism (distinct forms) is orchestrated in honeybees. They proposed that the default developmental pathway is the queen phenotype, and that the more Spartan diet of workers (less volume, lower fatty acid content and, particularly, lower carbohydrate content) relative to queen larvae, leads to the methylation of genes whose expression is then changed to generate worker morphology.

In the honeybee, behavioral castes can be experimentally created by simple manipulations of colony demography. For example, precocious foragers can be created by removing all the natural ones, which causes rapid maturation of nurse workers to foraging tasks. The methylation patterns in same-aged nurse workers and foragers were examined, including foragers that had been forced to revert to nursing. Each behavioral phenotype was associated with its own specifically methylated regions, and these regions were enriched for gene-regulatory functions. Importantly, foragers that had reverted back to nursing showed methylation patterns more similar to nurses than to foragers. Similar findings were shown for a set of eight genes in which methylation levels were more associated with behavioral task than with chronological age. Most recently, ultra-deep sequencing has shown that three genes, dynactin, nadrin and pcb1, show small but significant differences in methylation patterns in honeybees of different ages that perform different tasks (newly emerged, young, nursing, foraging).

Nutrition

Nutritionally induced expression changes in honey bees support the notion that environment is a decisive contributing factor in modulating global gene expression and consequently determining how an adult organism is assembled during development. Both influences genetic and environmental are important, not only for development, but also in evolution. Information about the environment can be transmitted across generations through epigenetic means, such as for example maternal effects. This process might occur via an ‘inherited bridging phenotype,’ a highly adapted set of cells from the previous generations representing an organized base upon which the environment(s) eventually would act. The honey bee female embryos and newly born larvae are in effect indistinguishable until they begin to feed on either worker jelly or royal jelly, which will set them on two contrasting developmental trajectories. Hence young, up to 2-day-old, larvae represent the responsive ‘inherited bridging phenotype’ upon which the nutritional cues can act to instruct the genome how to assemble an appropriate adult. The resulting conditional phenotype is a product of a gene x environment interaction whereby the genome places boundary conditions on the possible structures that can unfold during embryogenesis but responds in a flexible manner to changing conditions during larval stages. The newly born female larva is constrained by its inherited genomic hardware but has considerable developmental flexibility in terms of its epigenetic software that is used for integration of environmental and genomic influences. The ability by members of a colony to produce a special diet was a key evolutionary invention that created a well-defined environmental trait that persists across generations. An epigenetic mechanism was used for capturing environmental information to inform ontogeny.

Caste determination is the focus in larval development while behavioral transition of adult workers is the focus in adult nutrition. The honey bee queen and brood need to be fed by workers with secretions from the worker’s HPG and mandibular gland (MDG). Therefore, the nutrition of the queen and larvae is fully controlled and manipulated by worker feeding. Honey bee brood rearing and adult bee survival exclusively depend on food stores in the colony. Adult behavior such as brood feeding, age at onset of foraging, and foraging preference is regulated by colony needs and also by the adults’ own nutritional status.

Royal Jelly

Early diets in honeybees have effects on epigenome with consequences on their phenotype. Depending on the early larval diet, either royal jelly (RJ) or royal worker, 2 different female castes are generated from identical genomes, a long-lived queen with fully developed ovaries and a short-lived functionally sterile worker. To generate these prominent physiological and morphological differences between queen and worker, honeybees utilize epigenetic mechanisms which are controlled by nutritional input. These mechanisms include DNA methylation and histone post-translational modifications, mainly histone acetylation. In honeybee larvae, DNA methylation and histone acetylation may be differentially altered by RJ. This diet has biologically active ingredients with inhibitory effects on the de novo methyltransferase DNMT3A or the histone deacetylase 3 HDAC3 to create and maintain the epigenetic state necessary for developing larvae to generate a queen.

The discovery of a family of highly conserved DNA cytosine methylases in honey bees and other insects suggests that, like mammals, invertebrates possess a mechanism for storing epigenetic information that controls heritable states of gene expression. Recent data also show that silencing DNA methylation in young larvae mimics the effects of nutrition on early developmental processes that determine the reproductive fate of honey bee females.

The ability to produce contrasting phenotypes from the same DNA genome in the absence of mutation is one of the key inventions in eukaryotic evolution and is often taken for granted at the cellular level. For example, the different cell types that make up the human body have the same DNA genome, but their very different cellular phenotypes are brought about by differential epigenetic events, largely during embryogenesis. Subsequently, human metabolism, aging and behavior is due to changes in epigenetic properties as a result of environmental signals and the responses of epigenomic receivers in different tissues and organs.

It is widely accepted that the remarkable biological potency of royal jelly is at least partly attributable to a group of proteins known as the Major Royal Jelly Proteins (MRJPs). In the bee genome, MRJPs are encoded by an array of nine genes belonging to the yellow family which are clustered in the same chromosomal region. This yellow gene family performs diverse functions related to pigmentation, development and sexual maturation in insects. The genomic architecture of the yellow/royal jelly gene family in the honey bee suggests that in ancestral bees subsequent duplications of one member of the yellow cluster produced a new gene family (royal jelly), which evolved new functions relevant to social behavior.

It is also widely accepted that a high royal jelly intake by a feeding larva is sensed by the gut epithelium and then metabolized in larval fat body (an insect ‘liver’). This cue activates the insulin pathway, which in turn increases the level of a hormone controlling some metabolic subnetworks. The activation of such networks results in a rapid utilization of the available nutrients and leads to an increased demand for even more food. Thus, the system stimulates larval growth at an astonishing rate. Interestingly, the same hormone (juvenile hormone) that activates these metabolic subnetworks has a contrasting inhibitory effect on the development of certain organs that would be useless for a queen, such as the royal jelly producing glands, or pollen collecting baskets.

The evolutionary advent of the royal jelly proteins solved two difficult problems: (1) how to ensure that a cue used to control a non-genetic queen/worker dimorphism was faithfully transmitted across generations, and (2) how to provide the hungry queen larva with essential but limiting nutrients.

Conclusion

Research in many scientific areas clearly indicate that environmental pressures cause change. Amazingly a species’ genes hold the ability to respond to these and survive based on physiological adaptions of historical environmental pressures. What is unlikely recognized by the beekeeper is the fact that everything they do presents additional environmental pressures the bees have to address and in this short timeframe of their evolution are genetically not adapted for. For example, the honey bee’s life is always focused on reproduction and at the center of this is the queen. So, the health of the queen, her ability to lay, and the availability of resources for larvae is of critical importance. This is a cycle that has gone on for over a million years and one that the bees have become very good at. Over their history they have faced and overcome climate changes, pests and pathogens but until recent centuries have not had to deal with man. Does off season feeding and brood rearing , swapping out healthy queens, continual exposure to chemical treatments, introduction of drugs, yard treatments, monocultures, constant destruction of the hive homeostasis environment, and breeding for genetics that suit beekeepers’ verses bee’s survival introduce new evolutionary challenges that make bees survival uncertain? Everything we do affects the bees, so this saying is very important to remember…

We have never known what we were doing because we have never known what we were undoing.

We cannot know what we are doing until we know what nature would be doing if we were doing nothing.

~Wendell Berry, “Preserving Wilderness” 1987

Reference Materials

- Phenotypic plasticity in development and evolution: facts and concepts

- Polyphenism in Insects

- Epigenetics, plasticity, and evolution: How do we link epigenetic change to phenotype?

- Epigenetics and Developmental Plasticity Across Species

- How does epigenetics influence the course of evolution?

- DNA is the ultimate blueprint— but epigenetics changes how it’s read

- Epigenetics

- The genomic basis of evolutionary differentiation among honey bees

- Honeybee or Queen: A Study of the Epigenetic Differentiation of Bees

- Epigenetic Modification of Gene Expression in Honey Bees by Heterospecific Gland Secretions

- Gene expression and epigenetics reveal species-specific mechanisms acting upon common molecular pathways in the evolution of task division in bees

- Epigenomic communication systems in humans and honey bees: From molecules to behavior

- The role of epigenetics, particularly DNA methylation, in the evolution of caste in insect societies

- Epigenetic integration of environmental and genomic signals in honey bees: the critical interplay of nutritional, brain and reproductive networks

- The diverging epigenomic landscapes of honeybee queens and workers revealed by multiomic sequencing

- Epigenetic regulation of the honey bee transcriptome: unravelling the nature of methylated genes

- Epigenetics Mechanisms of Honeybees: Secrets of Royal Jelly

- Physiological and Molecular Mechanisms of Nutrition in Honey Bees

- Epigenetic regulation of the honey bee transcriptome: Unraveling the nature of methylated genes

- Epigenetic patterns determine if honeybee larvae become queens or workers